Basic income is a regular cash payment to members of a community, without a work requirement or other conditions.

What is Basic Income?

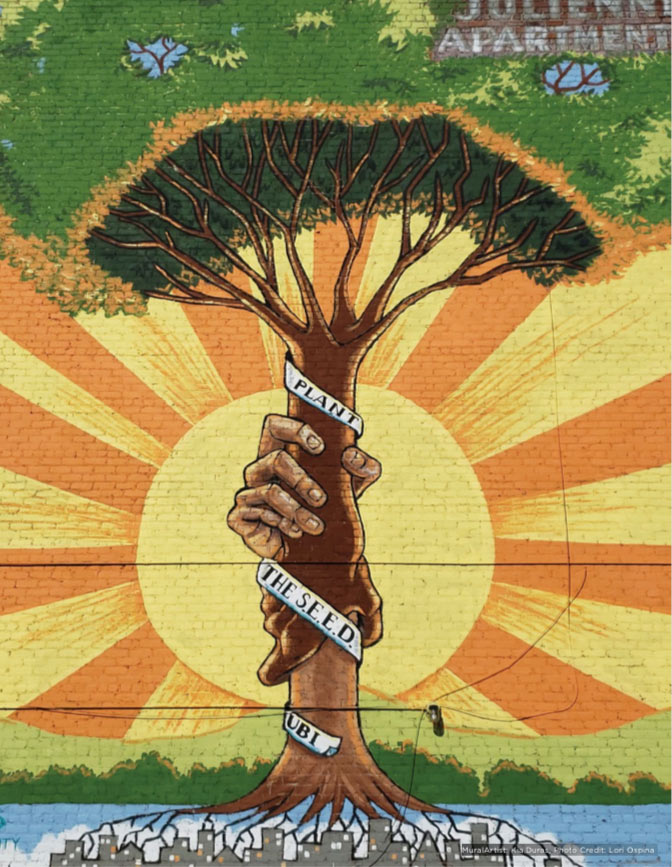

Basic income takes on distinct forms in different historical and geographic contexts. It varies based on the funding proposal, the level of payment, the frequency of payment, and the particular policies proposed around it. Each of these parameters are fundamental, even if a range of versions qualify as basic income. Universal Basic Income, or UBI, can be defined as a universal, unconditional, individual, regular and cash payment to all members of a community. Guaranteed Income, or GI, is an unconditional, periodic, cash payment that is targeted to specific residents within a community, typically those below some income threshold, sometimes targeted based on other criteria as well (for example, single parents with children).History of Basic Income

From Bidadanure, Juliana Uhuru. (2019). “The Political Theory of Universal Basic Income.” Annual Review of Political Science 22, no. 1 (May 11, 2019): 481–501.

In recent years, UBI went from a utopian proposal to a policy with growing currency. UBI experiments have been conducted in countries as different as Kenya, Finland, Namibia, India, and Canada. In the United States, variants of the UBI proposal were very much alive in the early second half of the twentieth century—including through figures like Martin Luther King, Jr., and Milton Friedman—but the conversation did not pick up much in subsequent decades.

This changed around 2016, when several American personalities wrote on the policy, including former Service Employees International Union president Andrew Stern, former Secretary of Labor Robert B. Reich, and futurist Martin Ford. Notably, the technology incubator Y Combinator started testing UBI in Oakland, California, in 2016; the Economic Security Project was launched in 2016, devoting millions of dollars to research and advocacy on UBI; and the mayor of Stockton, California, announced the launch of a pilot program, subsequently launched in March 2019.

The growth of income and wealth inequalities, the precariousness of labor, and the persistence of abject poverty have all been important drivers of renewed interest in UBI in the United States. But it is without a doubt the fear that automation may displace workers from the labor market at unprecedented rates that primarily explains the revival of the policy, including by many in or around Silicon Valley (Ford 2015).

UBI has a long history and has been defended from a variety of often overlapping, but occasionally conflicting, ideological perspectives. Like most proposals to expand the safety net, UBI has roots in social democratic, anarchist, and socialist thinking. Ancestors of UBI were discussed by the likes of Thomas Paine (1797) in the form of a lump sum granted to all citizens at adulthood, the Belgian socialist Joseph Charlier (1848) in the form of a “territorial dividend” generating a regular income, and James Meade [1988 (1935), 1993 (1964)] in the form of a “social dividend” in the 1930s and later. Those proposals share with recent versions of UBI a commitment to the view that a share of the wealth produced by all in common, or by previous generations, should be redistributed to all in the form of a direct payment to individuals.

In the context of systemic discrimination against African Americans and resulting widespread unemployment and poverty, the National Welfare Rights Organizations (with leaders such as Beulah Sanders, Jennette Washington, and Johnnie Tillmon), Martin Luther King, Jr., the Black Panther Party, and James Boggs (1968) all considered and pushed for versions of guaranteed income as a tool of economic justice.

Meanwhile, feminists, including the Wages for Housework movement in the 1970s, also discussed an income separate from labor as a way to weaken the prominence of the male breadwinner model (Costa & James 1973, Cox & Federici 1976). UBI also has a footing in neoliberal thinking. The economist Milton Friedman famously defended a cousin of UBI, the Negative Income Tax (NIT). He held that the NIT would raise the floor without negatively affecting the price system and market mechanisms, and that it would reduce the paternalistic and intrusive state bureaucracy required to decide who, among the poor, merits assistance (Friedman 1962, 1968).

Defining Characteristics

Features of basic income

Cash payment

It is paid in cash, allowing the recipients to convert their benefits into whatever they may like.

Unconditional

It involves no work requirement or sanctions; it is accessible to those in work and out of work, voluntarily or not.

Periodic

It is a recurrent payment (for example every month), rather than a one-off grant.